The shortage of physicians is getting worse. For as long as I’ve been writing this blog, I’ve been commenting on the shortage of physicians. Sadly, the situation is getting worse. But the solution to this dilemma is complex. There are many reasons for this shortage and solving the problem will require addressing each of these.

Not Enough Doctors or Medical School Seats

A.R. Cabral, writing for USNews.com, tells us of the comments of Dr. Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, president of the American Medical Association, who told the National Press Club in the fall of 2023, “Imagine walking into an emergency room in your moment of crisis – in desperate need of a physicians’ care – and finding no one there to take care of you,” he said. This situation is not far-fetched in some rural areas especially.

The demand for licensed physicians is at an all-time high and projected to be significantly higher by 2034, largely due to a growing and aging population. Many observers wonder if admitting more students into medical schools will address the scarcity. But that means more medical schools, larger faculties to teach those students, and more applicants of high quality to fill those seats.

In January 2024, there were just above 1.1 million professionally active doctors in the U.S., according to Statista, a worldwide data and business intelligence platform. And tens of thousands of those licensed physicians spend more time teaching, in research or in administrative roles than in patient care, according to the American Medical Association. Per the National Association of Community Health Centers, the physician shortage means 30% of Americans don’t have a regular primary care doctor.

That’s also a problem for medical schools: In short, you need doctors to make doctors. A shortage of them limits the number of mentors, teachers and attending physicians – for clinical hours – to engage with medical students. This is a consideration when increasing enrollment at medical schools, which number fewer than 200 in terms of accreditation to grant an M.D. or doctor of osteopathic medicine degree in the U.S.

A. Dexter Samuels, executive director of the Center for Health Policy at Meharry Medical School in Tennessee, echoes concerns. Admitting more students would disrupt the ratio of faculty to students, he says. For every med student, a slot should be available for training in a hospital setting. The doctor shortage can’t accommodate an increase in the number of students, Samuels says, and “hypercompetitiveness of recruiting and retaining faculty” is an ongoing challenge.

Already, fewer than half of all applicants to U.S. med schools are accepted each year, with the average hopeful applying to multiple schools. Solving the doctor shortage in the U.S. will take more than just increasing the number of spots available in medical school, says Dr. Amy Waer, dean of Texas A&M University’s School of Medicine. That’s because there’s a bottleneck between medical school and graduate medical education – that is, residencies and fellowships – also known as GME.

“While many medical schools would like to increase their admission numbers, finding appropriate clinical training sites and physician faculty are limiting factors, particularly for community-based medical schools like Texas A&M,” Waer wrote in an email.

Per the Association of American Medical Colleges, residency slots and clinical training sites haven’t kept pace with growing medical school enrollments – and without residency training, graduating doctors can’t be licensed to treat patients. Experts say the shortfall is largely due to a congressionally imposed cap on federal support for GME through the Medicare program, in place since 1997.

Medical School Enrollment

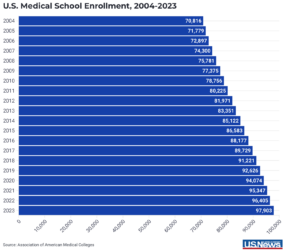

Enrollment in M.D.-granting medical schools has grown steadily from 92,626 during the 2019-2020 school year to 97,903 in 2023-2024, according to AAMC data. That’s up significantly from 69,718 med school students in 2002, per the AAMC.

However, the increases are unlikely to fully address the scarcity of doctors predicted through 2034. The class sizes, enrollment and number of medical schools are “not growing fast enough to meet the demand for physicians’ services and health care across the nation,” Ehrenfeld says.

New medical schools are opening, aiming to produce more doctors. They will also benefit their surrounding communities, Ehrenfeld says. “Schools have different missions and different goals they are trying to achieve,” he says. “As there continue to be innovative solutions around medical education and meeting those demands, we will see more campuses and more schools trying to align the needs of the community with the mission of the program.”

Unfortunately, some medical schools are resorting to “wokeness” to find more medical school applicants, lowering the bar for qualification. For more on this read my post called Rejecting Wokeness in Medical Schools. The solution to the shortage of physicians is not accepting less qualified applicants of any race or socioeconomic background. It is incentivizing the best of our youth to pursue a medical career so we have an abundance of highly qualified physicians. I favor government subsidized medical education. If we want the best doctors, we have to be willing to make it easy for anyone who is qualified to go to medical school. We also must make larger investments in medical school facilities to meet the challenge of physician shortages.